The humanities are in crisis! The crisis seems to be that the number of students who choose to study humanities subjects in college is in steep decline, as more students pursue majors in professional fields, like business, or STEM subjects, because these subjects are widely seen by students to be better job training. Some argue that this is because our society has devalued creative and culturally generative work. To some, the narrow focus on employment and earnings is cause for lament and alarm. Others suggest that the decline is overstated, and that the humanities had a brief, anomalous post-war period of popularity.

There are, I imagine, as many suggestions for how to reverse this crisis as there are proposed reasons for its cause. I merely want to point out that this brief "golden age" of interest in the humanities, followed by a period of greater interest in professional training has happened before...at the outset of the first universities in Europe. In the twelfth century, the great cathedral schools at Chatres and Orléans placed particular emphasis on ancient literature and neoplatonist philosophy. In these places, "the spirit of a real humanism showed itself in an enthusiastic study of ancient authors and in the production of Latin verse of a really remarkable quality."* But this humanistic renaissance was ultimately short lived, as interest in the science of logic and the professional fields of law and medicine prevailed over interest in literature and philosophy. John of Salisbury, in the late twelfth century, complained that the logic masters knew almost nothing of literature. Fifty years later, Henri d'Andeli, a French poet, wrote that "Logic has the students, whereas Grammar [literature] is reduced in numbers, Civil Law rode gorgeously and Canon Law rode haughtily ahead of all the other arts."* Medieval is the new modern, people!

* Taken from C. H. Haskins, The Rise of Universities, ch. 2.

Monday, December 16, 2013

Friday, December 13, 2013

The Year in Robots

I've been doing some sifting through the year's news stories about robotics and robots to do a round-up post. But then I came across Lewis Black's segment on last night's Daily Show and thought, why bother?

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Chess & Mind

I recently started learning something new:

chess.

I never played it, I didn't know anyone who played it, and my total exposure to chess came from books and films in which people played chess (see: Searching for Bobby Fischer, Fresh, The Lymond Chronicles (especially Pawn in Frankincense), The Americans, Cairo Time, WarGames, The West Wing, etc.). In the cultural artifacts that introduced me to the game, it was always heralded as something really hard. When a character plays chess in a story, it tells the audience that the person (Fresh, Jed Bartlet, or Francis Crawford) playing is always several steps ahead of the people around them. Chess players think ahead, they can strategize, they can "see the whole board." And the mathematical nature of chess, especially (so I'm told) at its highest levels, lends itself to computational technology. (I vividly remember the Kasparov-Deep Blue matchup.)

But I confess that I'm confused about how and why chess became a yardstick for intelligence and, in some cases, for humanity, insofar as "human intelligence" is a proxy for what makes us uniquely human. Humans have been building calculating machines for millennia--even before chess was invented. Why is it that the element of human intelligence that is the *easiest* to reproduce with machinery became associated with chess, and used as a marker for intelligence itself? When did this start to happen? And what does this reveal about historical theories of mind and cognition--have they changed sufficiently over the past centuries to reveal any changes in terms of the importance chess as a measure of intellectual capability?

chess.

|

| The Lewis Chessmen. |

I never played it, I didn't know anyone who played it, and my total exposure to chess came from books and films in which people played chess (see: Searching for Bobby Fischer, Fresh, The Lymond Chronicles (especially Pawn in Frankincense), The Americans, Cairo Time, WarGames, The West Wing, etc.). In the cultural artifacts that introduced me to the game, it was always heralded as something really hard. When a character plays chess in a story, it tells the audience that the person (Fresh, Jed Bartlet, or Francis Crawford) playing is always several steps ahead of the people around them. Chess players think ahead, they can strategize, they can "see the whole board." And the mathematical nature of chess, especially (so I'm told) at its highest levels, lends itself to computational technology. (I vividly remember the Kasparov-Deep Blue matchup.)

But I confess that I'm confused about how and why chess became a yardstick for intelligence and, in some cases, for humanity, insofar as "human intelligence" is a proxy for what makes us uniquely human. Humans have been building calculating machines for millennia--even before chess was invented. Why is it that the element of human intelligence that is the *easiest* to reproduce with machinery became associated with chess, and used as a marker for intelligence itself? When did this start to happen? And what does this reveal about historical theories of mind and cognition--have they changed sufficiently over the past centuries to reveal any changes in terms of the importance chess as a measure of intellectual capability?

Friday, November 8, 2013

Robots from Days Gone By

Amazing automata from ye olden times have been cropping up everywhere recently! The New York Times recently ran an article about the creations of R. J. Wensley, a robotics engineer and inventor from the first half of the 20th century.* And then the folks at Colossal got excited about Simon Schaeffer's recent (and fabulous) BBC documentary, and a few of the 18th century automata that he profiles. One of these, L'écrivain, is from the workshop of Pierre & Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz. Adelheid Voskuhl has a recent piece in Slate about the importance of the Jaquet-Droz and other Enlightenment

automata.Voskuhl's argument, based on her recent (and fabulous) book Androids in the Enlightenment, is that these luxury objects actually modeled new forms of civic engagement and social behavior by performing affective practices that were important to bourgeois and aristocratic Enlightenment culture. These automata, especially the piano-playing women that Voskuhl focuses on in her book, are conceptually similar to the 16th century praying monk, commissioned by King Charles V of Spain, that demonstrated proper devotional practice, and to the imaginary figures from the Alabaster Chamber in the 12th-century Roman de Troie, which enacted and enforced courtly behavior.

* While I'm always happy to see Leonardo get name-checked, esp. in relation to early automata, it goes without saying that the *entire point of this blog* is to make it clear that these objects were imagined and built well before the fifteenth century.

automata.Voskuhl's argument, based on her recent (and fabulous) book Androids in the Enlightenment, is that these luxury objects actually modeled new forms of civic engagement and social behavior by performing affective practices that were important to bourgeois and aristocratic Enlightenment culture. These automata, especially the piano-playing women that Voskuhl focuses on in her book, are conceptually similar to the 16th century praying monk, commissioned by King Charles V of Spain, that demonstrated proper devotional practice, and to the imaginary figures from the Alabaster Chamber in the 12th-century Roman de Troie, which enacted and enforced courtly behavior.

* While I'm always happy to see Leonardo get name-checked, esp. in relation to early automata, it goes without saying that the *entire point of this blog* is to make it clear that these objects were imagined and built well before the fifteenth century.

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

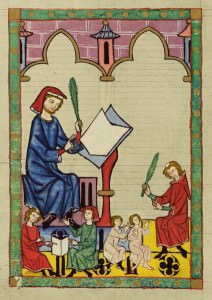

The Sad State of Education, 12th-Century Edition

I recently had the good fortune to examine LJS 384 (an early copy of William of Conches' De philosophia mundi and an excerpt of Hugh of St. Victor's commentary on the Gospels) in more detail. Doing so gave me the opportunity to spend some time researching William and De philosophia.

It turns out that William, a student of and teacher at the cathedral school at Chartres in the early twelfth century, had a lot to say about the sorry state of education. William had been taught by Bernard of Chartres and his cohort in the early twelfth century. But by the time William was teaching students a decade later, he realized that the golden age of learning had passed. Men now call themselves philosophers, he said, but they disdain to learn from anyone and are too arrogant to admit their ignorance.* Students flock to study philosophy in ever greater numbers so that teachers are so preoccupied with teaching that they have little time for research and writing. And teachers are so dependent on their students' good opinion of them that they offer easy courses. "Masters are become flatterers of their students and students judges of their masters."**

Truly, the End Times of advanced education have always been with us.

*This sounds like a veiled barb directed at Abelard, no?

**The info in the paragraph--and much more--can be found in volume 2 of Lynn Thorndike's History of Magic and Experimental Science.

It turns out that William, a student of and teacher at the cathedral school at Chartres in the early twelfth century, had a lot to say about the sorry state of education. William had been taught by Bernard of Chartres and his cohort in the early twelfth century. But by the time William was teaching students a decade later, he realized that the golden age of learning had passed. Men now call themselves philosophers, he said, but they disdain to learn from anyone and are too arrogant to admit their ignorance.* Students flock to study philosophy in ever greater numbers so that teachers are so preoccupied with teaching that they have little time for research and writing. And teachers are so dependent on their students' good opinion of them that they offer easy courses. "Masters are become flatterers of their students and students judges of their masters."**

Truly, the End Times of advanced education have always been with us.

*This sounds like a veiled barb directed at Abelard, no?

**The info in the paragraph--and much more--can be found in volume 2 of Lynn Thorndike's History of Magic and Experimental Science.

Aaaaaand, We're Back!

Sorry for the radio silence. I've been finishing the book of medieval robots. Still a long road ahead, but I'm closer than before. Watch this space for more details as they emerge!

Thursday, August 15, 2013

Roll Call

I've updated the blog roll and added some goodies:

The Recipe Project has great posts and links on early modern recipes and "food, science, magic, and medicine."

Generation to Reproduction is the go-to site for info and research from the multi-disciplinary History of Reproduction group at the University of Cambridge, like the piece on the Middle English gynecological text, "The Sekeness of Wymmen."

Queens in the Middle Ages has syllabi, bibliographies, and reviews of everything having to do with queenship and female rulership in the medieval period.

The Renaissance Mathematicus answers many of your questions about early modern science, and Contagions gives you the lowdown on the history of infectious diseases, like the plague.

The New York Academy of Medicine site has articles from scholars about their research, like this recent piece about one scholar's ongoing work with a particular manuscript.

And, finally, Peter Adamson will tell you everything you need to know about the history of western philosophy, including medieval philosophy in the Christian, Islamic, and Jewish traditions.

Additionally, here's a great translation of a 15th century Arabic text on body oils, in case the summer heat has left your skin a bit parched.

The Recipe Project has great posts and links on early modern recipes and "food, science, magic, and medicine."

Generation to Reproduction is the go-to site for info and research from the multi-disciplinary History of Reproduction group at the University of Cambridge, like the piece on the Middle English gynecological text, "The Sekeness of Wymmen."

Queens in the Middle Ages has syllabi, bibliographies, and reviews of everything having to do with queenship and female rulership in the medieval period.

The Renaissance Mathematicus answers many of your questions about early modern science, and Contagions gives you the lowdown on the history of infectious diseases, like the plague.

The New York Academy of Medicine site has articles from scholars about their research, like this recent piece about one scholar's ongoing work with a particular manuscript.

And, finally, Peter Adamson will tell you everything you need to know about the history of western philosophy, including medieval philosophy in the Christian, Islamic, and Jewish traditions.

Additionally, here's a great translation of a 15th century Arabic text on body oils, in case the summer heat has left your skin a bit parched.

Thursday, August 8, 2013

The Alpha and Omega of Human Artifice

H/t to MB, one of Medieval Robots' LA correspondents, for drawing my attention to this mind-blowing ad for the Omega Co-Axial Chronometer. For those of you not completely au courant with horological developments in recent decades, Omega introduced the Co-Axial escapement in 1999, when it was the first new significant development in mechanical watch movement technology in centuries.*

Visually similar to the opening credit sequence to "Game of Thrones," the ad also hits some important and longstanding themes from the intersection of art and technology, especially horological timekeeping. The opening VO neatly encapsulates the possibility of human art perfecting (or perhaps surpassing) nature. The visuals, which meld natural and technological "movements" of different kinds, recall Martin Kemp's observation about the permeable boundaries, in Gothic and Renaissance art, between art and nature. And the final image of the mechanical orrery makes it clear that timekeeping--even in a wristwatch--is a way of mimicking the perfect movements of the heavens.

*The escapement is the mechanism that allows for the stored potential energy (in the case of a mechanical wristwatch, this energy is usually generated from winding a spring) to be released in regular increments.

Visually similar to the opening credit sequence to "Game of Thrones," the ad also hits some important and longstanding themes from the intersection of art and technology, especially horological timekeeping. The opening VO neatly encapsulates the possibility of human art perfecting (or perhaps surpassing) nature. The visuals, which meld natural and technological "movements" of different kinds, recall Martin Kemp's observation about the permeable boundaries, in Gothic and Renaissance art, between art and nature. And the final image of the mechanical orrery makes it clear that timekeeping--even in a wristwatch--is a way of mimicking the perfect movements of the heavens.

*The escapement is the mechanism that allows for the stored potential energy (in the case of a mechanical wristwatch, this energy is usually generated from winding a spring) to be released in regular increments.

Tuesday, July 23, 2013

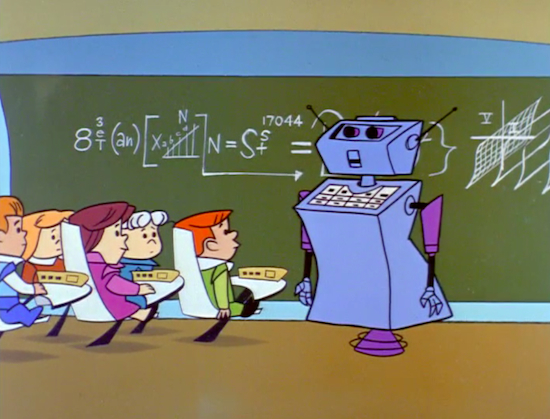

Professors Aren't Robots

Two great recent essays appeared in Inside Higher Ed in the past weeks that articulate the purposes and benefits of a college education, and also outline the major challenges to higher ed that no one is talking about.

The first essay, by Scott L. Newstok, eloquently describes the work that college professors do. He calls it "close learning."

"To state the obvious: there’s a living, human element to education. We who cherish in-person instruction would benefit from a pithy phrase to defend and promote this millennia-tested practice. I propose that we begin calling it "close learning." "Close learning" evokes the laborious, time-consuming, and costly but irreplaceable proximity between teacher and student. "Close learning" exposes the stark deficiencies of mass distance learning such as MOOCs, and its haste to reduce dynamism, responsiveness, presence."

I like the contrast with "distance learning," and Newstok's formulation recalls a colleague's assertion that SLACs are the "slow food movement" of higher education.

In the second essay, the author, Matthew Pratt Guterl, ardently defends the ceaseless student-professor interactions that take place in the classroom, the hallway, the office, and in the margins of student essays. As our public universities receive less and less public funding, and are more and more reliant on cutting costs, departments are pressured to offer large intro courses without suitable staffing or critical administrative support. This eats into the time and opportunities that professors have to teach skills and habits of mind, as opposed to offering content.

"But this "honors-style" dream was chipped away slowly by the annual news reports of state budget cuts. We were pressed to create bigger courses, to put "fannies in the seats." We ended our enhanced foreign language requirement because it kept our major count down. We were encouraged to open up our enrollments, to create a big survey course at the front end of the major, a course that became so large that we had to trim off the writing requirement and give multiple-choice exams. We spent hours on assessment data, all required by the state higher education board, and less and less, as a consequence on students."

Both writers point to the fact that teaching isn't scalable, and that the people who do it are, in fact, professionals. Additionally, Guterl links the de-funding of higher education to increasing costs--especially the costs of covering health care premiums for employees. I wonder why university presidents and administrators didn't lobby hard for a single-payer system a few years ago, as it would have done a lot to neutralize rapidly rising tuition costs. But go and read both essays for yourself. They're great.

The first essay, by Scott L. Newstok, eloquently describes the work that college professors do. He calls it "close learning."

"To state the obvious: there’s a living, human element to education. We who cherish in-person instruction would benefit from a pithy phrase to defend and promote this millennia-tested practice. I propose that we begin calling it "close learning." "Close learning" evokes the laborious, time-consuming, and costly but irreplaceable proximity between teacher and student. "Close learning" exposes the stark deficiencies of mass distance learning such as MOOCs, and its haste to reduce dynamism, responsiveness, presence."

I like the contrast with "distance learning," and Newstok's formulation recalls a colleague's assertion that SLACs are the "slow food movement" of higher education.

In the second essay, the author, Matthew Pratt Guterl, ardently defends the ceaseless student-professor interactions that take place in the classroom, the hallway, the office, and in the margins of student essays. As our public universities receive less and less public funding, and are more and more reliant on cutting costs, departments are pressured to offer large intro courses without suitable staffing or critical administrative support. This eats into the time and opportunities that professors have to teach skills and habits of mind, as opposed to offering content.

"But this "honors-style" dream was chipped away slowly by the annual news reports of state budget cuts. We were pressed to create bigger courses, to put "fannies in the seats." We ended our enhanced foreign language requirement because it kept our major count down. We were encouraged to open up our enrollments, to create a big survey course at the front end of the major, a course that became so large that we had to trim off the writing requirement and give multiple-choice exams. We spent hours on assessment data, all required by the state higher education board, and less and less, as a consequence on students."

Both writers point to the fact that teaching isn't scalable, and that the people who do it are, in fact, professionals. Additionally, Guterl links the de-funding of higher education to increasing costs--especially the costs of covering health care premiums for employees. I wonder why university presidents and administrators didn't lobby hard for a single-payer system a few years ago, as it would have done a lot to neutralize rapidly rising tuition costs. But go and read both essays for yourself. They're great.

Thursday, July 11, 2013

Dispatches from the Cam: "Medieval" = Awesome

The most recent issue of my Cambridge alumni magazine [sub. req'd.] has a great interview with Professor Helen Cooper about how the Middle Ages needs to be rescued from the ash-heap of history. She eloquently describes the effect of calling anything backwards, grim, or unpleasant "medieval," while attributing to the Renaissance all manner of wonderful things.

"No historical period simply finishes at one given moment....The influence of the medieval is pervasive and shaping right through to the middle of the 17th century and beyond. What I want to do is consciousness raising--so that people see what's too close up to them to notice."

Like: the invention of universities, double-entry book-keeping, mechanical clocks, the emergence of iconic fashion, and a representative democracy coupled with a parliament.

Preach it, Professor Cooper!

"No historical period simply finishes at one given moment....The influence of the medieval is pervasive and shaping right through to the middle of the 17th century and beyond. What I want to do is consciousness raising--so that people see what's too close up to them to notice."

Like: the invention of universities, double-entry book-keeping, mechanical clocks, the emergence of iconic fashion, and a representative democracy coupled with a parliament.

Preach it, Professor Cooper!

Thursday, June 13, 2013

A Visit to Schloss Hellbrunn

I recently had the good fortune to visit Schloss Hellbrunn, outside Salzburg. The palace has one of the oldest and most extensive collections of automata and trick fountains still in evidence (and still working). It was completely enchanting and also very illuminating.

Schloss Hellbrunn was built in the early 17th century, at the command of Archbishop Markus Sittikus. It was intended to be a "summer palace"--a place for the great and good of Salzburg to spend a summer afternoon, before returning to their homes in the city. The archbishop's guests would dine al fresco in the Roman Theater, surrounded by fountains and statues. The basin in the middle of the table keeps the wine chilled. And the table and seats have hidden water jets that would soak the guests (but not the archbishop). Remember, court etiquette dictates that one cannot rise from the table unless the highest-ranking person does so first. So the archbishop would stay dry and seated, while his guests had to master their surprise and discomfort...and remain seated, no matter what.

Guests could (and can) stroll into the palace grottoes, beginning with the Neptune Grotto. A statue of Neptune dominates the space, and the walls and ceiling are covered in a sort of marine mosaic, with tiny shells forming the tesserae.

At the foot of the Neptune statue, the Germaul rolls his eyes and sticks out his tongue at the visitors. This was Archbishop Sittikus' response to his critics.

Upon leaving the Neptune Grotto and the charming Germaul, you have the chance to get sprayed with water...again. And, after escaping from the grotto and standing safely outside...this happens:

In fact, one of the most interesting aspects of the Wasserspiele is how they force spectators into different spaces, in the hope of escaping the water, and, of course, it just ends up being yet another opportunity for a shower. The sense of not knowing what is coming next definitely keeps people (including me) off-balance. Some of the fountains are simply lovely, like these turtles, and pose no threat to the enchanted onlooker.

Delight, amazement, uncertainty, and suspicion mingle with one another; these emotions are punctuated by bursts of Schadenfreude when an unsuspecting person gets thoroughly soaked. (For example, during my tour, the brave souls who sat at the Royal Table spent the next hour looking like they'd wet their pants.)

Along the way are small tableaux quasi-vivants, illustrating scenes of artisanal labor and Classical myth. (Blogger won't let me upload the video, so this still shot will have to do.)

After many other stops along the way, the final attraction is the Crown Grotto (completed after Sittikus' death in 1618). The golden crown shoots up to the ceiling, driven by a jet of water. Eventually, it comes back down, representing (I think) the rise and fall of earthly power.

All of the Wasserspiele are hydraulic-powered. While much of the plumbing is now PVC (there are still some copper and lead pipes), the original pipes were made of wood.

Schloss Hellbrunn was built in the early 17th century, at the command of Archbishop Markus Sittikus. It was intended to be a "summer palace"--a place for the great and good of Salzburg to spend a summer afternoon, before returning to their homes in the city. The archbishop's guests would dine al fresco in the Roman Theater, surrounded by fountains and statues. The basin in the middle of the table keeps the wine chilled. And the table and seats have hidden water jets that would soak the guests (but not the archbishop). Remember, court etiquette dictates that one cannot rise from the table unless the highest-ranking person does so first. So the archbishop would stay dry and seated, while his guests had to master their surprise and discomfort...and remain seated, no matter what.

|

| The Royal Table in the Roman Theater. |

|

| A close up of the decoration in the Neptune Grotto. |

Upon leaving the Neptune Grotto and the charming Germaul, you have the chance to get sprayed with water...again. And, after escaping from the grotto and standing safely outside...this happens:

| ||

| Don't look up! |

Delight, amazement, uncertainty, and suspicion mingle with one another; these emotions are punctuated by bursts of Schadenfreude when an unsuspecting person gets thoroughly soaked. (For example, during my tour, the brave souls who sat at the Royal Table spent the next hour looking like they'd wet their pants.)

Along the way are small tableaux quasi-vivants, illustrating scenes of artisanal labor and Classical myth. (Blogger won't let me upload the video, so this still shot will have to do.)

|

| This is a scene of a couple grinding scissors. |

| ||||

| The crown falls back down. The spectators are amazed! |

|

| This might be the most amazing aspect of my entire visit. |

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

Check Out BBC Doc "Mechanical Marvels: Clockwork Dreams"

BBC Four just aired a cracking documentary on automata, written and presented by historian of science Simon Schaffer. It's really good, and you should watch it. It covers early clockwork machinery, jacquemarts (bell-ringers) and clockwork automata, minaturization, revolution, fraud, and the replacement of human workers with machines. I particularly liked the section on Schloss Hellbrunn (which I shall be visiting later this summer) and the way that the "Mechanical Theatre" depicts the nobility's idea of a utopian society, complete with perfectly regular laborers. Schaeffer makes some interesting connections to the fact that horological and artistic innovation rested mainly on low-paid, low-status artisanal workers; these artisanal workers ended up displacing themselves when captains of industry built machines, using the same principles as elaborate, richly decorated luxury automata, to replace human labor.

Schaffer's expertise as a scholar is in early modern science, and he concentrates in the documentary on the automata of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. I have a few small emendations to offer to Schaffer's narrative. Although it's true that the regularity of clockwork machinery became used as a metaphor to understand the human body in the early modern period, early modern automata were not the first to mimic natural forms. The ancient Greeks, especially in the Alexandrian School (3rd-1st centuries BCE) designed fabulous automata (driven by pneumatics and hydraulics, rather than the verge-and-foliot escapement and falling weight drive of the early modern period) in the forms of animals and people. And Arabic engineers, in the ninth and thirteenth centuries, wrote detailed treatises on how to build programmable, musical fountains; mechanical servants; and elaborate clocks. It's also interesting to note that in the Middle Ages, descriptions of automata in narrative texts often describe them as perfect servants and as enforcers of different kinds of behavior.

Still, the documentary is a treat, and if you're interested in automata, horology, or the history of technology, you should see it.

Schaffer's expertise as a scholar is in early modern science, and he concentrates in the documentary on the automata of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. I have a few small emendations to offer to Schaffer's narrative. Although it's true that the regularity of clockwork machinery became used as a metaphor to understand the human body in the early modern period, early modern automata were not the first to mimic natural forms. The ancient Greeks, especially in the Alexandrian School (3rd-1st centuries BCE) designed fabulous automata (driven by pneumatics and hydraulics, rather than the verge-and-foliot escapement and falling weight drive of the early modern period) in the forms of animals and people. And Arabic engineers, in the ninth and thirteenth centuries, wrote detailed treatises on how to build programmable, musical fountains; mechanical servants; and elaborate clocks. It's also interesting to note that in the Middle Ages, descriptions of automata in narrative texts often describe them as perfect servants and as enforcers of different kinds of behavior.

Still, the documentary is a treat, and if you're interested in automata, horology, or the history of technology, you should see it.

Thursday, May 30, 2013

MOOCs and the Liberal Arts

Nathan Heller's recent piece in The New Yorker about MOOCs at Harvard is fantastic. It's not as long as it could be (I rarely say that about New Yorker articles), but it at least introduces so many of the difficult questions that MOOCs raise about pedagogy, learning, and the purpose of college. One of the professors who is taking part in the Great Harvard MOOC Experiment is Gregory Nagy, retooling his Core (now GenEd) course on the ancient Greek hero. Nagy has revamped his hour lectures to much shorter ones, complete with video clips and animation. It sounds fantastic, and I remember, when I taught in the Core, how highly regarded Professor Nagy's course was. But even the most charismatic, experienced lecturer is still giving a lecture. It's been demonstrated, again and again, that students don't learn very much from lectures. Furthermore, as InsideHigherEd reports, a new study proves that students don't learn any more from a charismatic lecturer than a dud (though they think the more charismatic lecturer to be a more effective teacher). Beyond that, students apparently aren't motivated to show up for lectures. Heller quotes Harvard professor and former dean Harry Lewis as saying:

Students, if all you're going to do is lecture at them, no longer see any reason to show up to be lectured at.

If elite R1 institutions are the pioneers of MOOC-land, beginning to survey and map out terrain, small liberal arts colleges are mostly looking at maps of terra incognita (here be dragons). Wesleyan is one of the first SLACs to partner with Coursera; Maria Bustillos has an amazing piece in The Verge about her experience in "The Ancient Greeks," taught by Wesleyan professor Andrew Szegedy-Maszak. She includes a conversation with Professor Szegedy-Maszak about the course. As with the HarvardX Greek hero MOOC, the lectures are apparently fantastic. But Bustillos is very clear that the MOOC demanded nothing of her as a student; it was one-way content coming at her. Without a way to interact meaningfully and in a sustained manner with other students and the professors, the course was like watching a really good documentary. Interestingly, the professor himself acknowledges this when considering how developing the MOOC will affect his other classes:

I'm supposed to teach the Greek history survey at Wesleyan this coming fall, and I think that what I will do is to incorporate the course lectures as part of the assignment, use them as a sort of introduction, and then I'll have more class time to engage the students in discussion of some of the interpretive problems, and issues of the sources, that otherwise I would have to skim by. Here, the class is 80 minutes twice a week; we were very strongly advised to keep the Coursera lectures between 12-20 minutes.

The classroom discussion (or "close colloquy," as the Amherst College mission statement puts it) emerges here, and in Heller's article, as centrally important to a liberal arts education. Heller writes:

I had adopted again the double consciousness of classroom students: the strange transaction of watching someone who watches back, the eagerness to emanate support. Something magical and fragile was happening here, in the room. I didn't want to be the guy to break the spell.

As I've reflected back on the semester (and read my teaching evaluations), it seems to me that those moments of genuine shared conversation between students and faculty make an outsized impact on students. Modeling and fostering critical thinking, and showing students how rewarding and delightful it can be to have thoughtful, engaged intellectual conversations, is at the heart of what happens in the classroom. For example, one of the things I do as a teacher is draw attention to students' substitution of "I feel" when what they mean is "I think." This can be a difficult habit for them to break, but it gets us all thinking and talking about rhetorical strategies, the importance of vocabulary, and the many ways to approach a question or interpretation. I've heard, again and again, that this is one of the things that my students find thought-provoking and productive for their own conceptions of themselves as thinking (rather than feeling) beings. Likewise, the combination of reading, screening, discussion, and role-playing in my Medievalisms course got the students excited to learn from each other and also intellectually agile enough to make fascinating connections to all kinds of material. The final papers were imaginative, thoughtful, and analytical about everything from video games to "Kingdom of Heaven" to the potato.

Perhaps what MOOCs can do for the liberal arts curriculum is free us from the tyranny of content. If we can all accept that lectures are an imperfect way for students to learn (to learn either facts or skills), and that content itself is not as centrally important as it once was, then we might turn our attention in the classroom away from lecture and back toward close colloquy.

*This whole post doesn't even get into the many fantastic articles and blog posts on the issues of market forces, labor, and economic motives for MOOCs. So I shall just say that you should all read Aaron Bady on market forces and MOOCs, Susan Amussen and Allyson Poska over at Historiann on who benefits the most from MOOCs, and Kathleen Lowrey on the implications of MOOCs on labor practices and the pedagogical assumptions that MOOCs rest on.

Students, if all you're going to do is lecture at them, no longer see any reason to show up to be lectured at.

If elite R1 institutions are the pioneers of MOOC-land, beginning to survey and map out terrain, small liberal arts colleges are mostly looking at maps of terra incognita (here be dragons). Wesleyan is one of the first SLACs to partner with Coursera; Maria Bustillos has an amazing piece in The Verge about her experience in "The Ancient Greeks," taught by Wesleyan professor Andrew Szegedy-Maszak. She includes a conversation with Professor Szegedy-Maszak about the course. As with the HarvardX Greek hero MOOC, the lectures are apparently fantastic. But Bustillos is very clear that the MOOC demanded nothing of her as a student; it was one-way content coming at her. Without a way to interact meaningfully and in a sustained manner with other students and the professors, the course was like watching a really good documentary. Interestingly, the professor himself acknowledges this when considering how developing the MOOC will affect his other classes:

I'm supposed to teach the Greek history survey at Wesleyan this coming fall, and I think that what I will do is to incorporate the course lectures as part of the assignment, use them as a sort of introduction, and then I'll have more class time to engage the students in discussion of some of the interpretive problems, and issues of the sources, that otherwise I would have to skim by. Here, the class is 80 minutes twice a week; we were very strongly advised to keep the Coursera lectures between 12-20 minutes.

The classroom discussion (or "close colloquy," as the Amherst College mission statement puts it) emerges here, and in Heller's article, as centrally important to a liberal arts education. Heller writes:

I had adopted again the double consciousness of classroom students: the strange transaction of watching someone who watches back, the eagerness to emanate support. Something magical and fragile was happening here, in the room. I didn't want to be the guy to break the spell.

As I've reflected back on the semester (and read my teaching evaluations), it seems to me that those moments of genuine shared conversation between students and faculty make an outsized impact on students. Modeling and fostering critical thinking, and showing students how rewarding and delightful it can be to have thoughtful, engaged intellectual conversations, is at the heart of what happens in the classroom. For example, one of the things I do as a teacher is draw attention to students' substitution of "I feel" when what they mean is "I think." This can be a difficult habit for them to break, but it gets us all thinking and talking about rhetorical strategies, the importance of vocabulary, and the many ways to approach a question or interpretation. I've heard, again and again, that this is one of the things that my students find thought-provoking and productive for their own conceptions of themselves as thinking (rather than feeling) beings. Likewise, the combination of reading, screening, discussion, and role-playing in my Medievalisms course got the students excited to learn from each other and also intellectually agile enough to make fascinating connections to all kinds of material. The final papers were imaginative, thoughtful, and analytical about everything from video games to "Kingdom of Heaven" to the potato.

Perhaps what MOOCs can do for the liberal arts curriculum is free us from the tyranny of content. If we can all accept that lectures are an imperfect way for students to learn (to learn either facts or skills), and that content itself is not as centrally important as it once was, then we might turn our attention in the classroom away from lecture and back toward close colloquy.

*This whole post doesn't even get into the many fantastic articles and blog posts on the issues of market forces, labor, and economic motives for MOOCs. So I shall just say that you should all read Aaron Bady on market forces and MOOCs, Susan Amussen and Allyson Poska over at Historiann on who benefits the most from MOOCs, and Kathleen Lowrey on the implications of MOOCs on labor practices and the pedagogical assumptions that MOOCs rest on.

Thursday, May 23, 2013

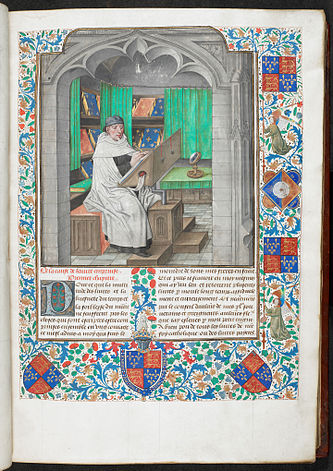

Game of Thrones as Universal History

|

| Vincent of Beauvais writing his universal history. BL MS Royal 14 E.i |

These chronicles are a particular and rather weird genre. There is no overarching narrative (although they were often written to legitimate particular dynasties). Chronicles contain dozens, even hundreds, of characters, and they appear and then disappear with no fanfare. There are long stretches of description and exposition punctuated by shocking or terrible events (poisoning, beheading, treason, famine, war). Occasionally, the writer pauses for a digression...a love story, a convoluted plot, an accusation of sorcery. Chronicles end abruptly and often without any kind of denouement. And because universal histories cover synchronous events in different locales, the authors constantly need to signal that the next episode in the chronicle is happening contemporaneously with something else.

A Song of Ice and Fire is a universal history. Martin has created a world with an elaborate backstory and its own mythology. The books encompass the history of Westeros and include the dynastic tales of the Targaryens and the Andals. The shifting POV chapters ensure that the chronicle covers synchronous events. There are hundreds of characters, long stretches of description and exposition, digressions on sorcery or love or treason. Characters that we have gotten to know over hundreds of pages die suddenly...and the story keeps moving. This mirrors universal histories; someone is always getting shot with a stray arrow or choking on a plate of eels at the inopportune moment. Rains of blood, fiery portents, and magical occurrences appear in chronicles; Game of Thrones opens with wights and ends with the marvelous rebirth of dragons, and the dead stag and direwolf of the opening portend the fates of Robert Baratheon and Ned Stark.

The chronicle-nature of Game of Thrones accounts for its strengths and its weaknesses. It's what makes the show so rich and multi-layered, but it also means that there many characters and plots. It's hard to keep track of everyone, and it's also difficult to link the pieces into a larger narrative. So far, Benioff and Weiss are doing a good job, although I wonder how the show will change as the story gets even more complicated. It's also why there are so many digressions in the books (Meereen, anyone?). I'll be interested to see if GRRM will bring any closure or denouement to ASoIaF over the next two books, or if he'll just write "explicitus est liber" and be done with it.

Thursday, May 9, 2013

Further Tales from The Library

I had a rare treat this afternoon: I went to the brand, spanking-new Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies at Penn. The space is gorgeous and fantastic for working; the library staff are helpful and knowledgeable; and the collection of scientific manuscripts is UNBELIEVABLE. Some of today's highlights included examining an early twelfth-century copy of Gerbert of Aurillac's introduction to geometry, the Isagogae geometriae. The manuscript has intralinear and marginal glosses, as well as manicula, in at least three different hands.

Another gem was a twelfth-century French copy of William of Conches' De philosophia mundi, with some fantastic diagrams, including this climate zone map. And further along, a monk took exception to the sections on procreation and childbearing.

|

| Geometry is more fun with dragons. LJS 194, fol. 7v. |

|

| The scribe wrote around a hole in the parchment, likely made during stretching. |

| |

| A Macrobian climate zone map. LJS 384, fol. 15r. |

|

| No ladyparts please, we're monks. LJS 384, fol. 16r. |

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

Notes from The Pedagogue's Desk

Several weeks ago, we began a new unit in the Medievalisms course that I'm teaching this semester. It's on fantasy and fan culture: First, the students watched an episode of Game of Thrones, read this fantastic review essay in the LRB, and did a bunch of internet research on the fansites and wiki sites around ASoIaF. Then they read Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks by Ethan Gilsdorf. Ethan visited class and led a lively and productive conversation about nerd culture, medievalism, fantasy, and role-playing. The following day, Ethan gave a talk to the larger community about the links between college culture and fantasy medievalisms, and then designed and led an evening D&D class.

My co-professor and I are newbs to RPGs, tabletop or otherwise, and we were entirely uncertain, when we first designed the syllabus, how this part of the course would come together.

It was fantastic.

The first half of this unit, on Game of Thrones and fan culture, got students thinking about the fantasy genre and medievalism. It has been challenging, throughout the semester, to help the students move beyond making arguments about accuracy and authenticity (or fidelity). However, once "accuracy" is off the table, as with fantasy, they immediately started to see the different medievalisms at play. The students were able to take the conversation further when they discussed Ethan's book with him, and they were *amazing* at the D&D session. Every single student got really into it, even the skeptics, and they were thoughtful and incisive the next day. They discussed questions of gender, performance, community and expertise, and medievalism, and analyzed their own experiences with the quest that Ethan designed.

The moral of this story: Engage with what the students are interested in (all of the students are interested in medievalism, having read Harry Potter or watched LOTR; others are intense and frequent gamers or LARPers), and then bring in a really smart person to help you with what you don't know about.

My co-professor and I are newbs to RPGs, tabletop or otherwise, and we were entirely uncertain, when we first designed the syllabus, how this part of the course would come together.

It was fantastic.

The first half of this unit, on Game of Thrones and fan culture, got students thinking about the fantasy genre and medievalism. It has been challenging, throughout the semester, to help the students move beyond making arguments about accuracy and authenticity (or fidelity). However, once "accuracy" is off the table, as with fantasy, they immediately started to see the different medievalisms at play. The students were able to take the conversation further when they discussed Ethan's book with him, and they were *amazing* at the D&D session. Every single student got really into it, even the skeptics, and they were thoughtful and incisive the next day. They discussed questions of gender, performance, community and expertise, and medievalism, and analyzed their own experiences with the quest that Ethan designed.

The moral of this story: Engage with what the students are interested in (all of the students are interested in medievalism, having read Harry Potter or watched LOTR; others are intense and frequent gamers or LARPers), and then bring in a really smart person to help you with what you don't know about.

Sunday, April 21, 2013

Not Content

Recent articles and incisive blog posts about MOOCs, alongside few more recent news articles that present different ideas about the purpose of higher education in this country have vividly illustrated the shift to thinking about education as content and students as users. I don't have a lot to add to Historiann's fantastic close reading of the decision of Amherst faculty to turn down the opportunity to partner with EdX; however, it's notable that this story hit Inside Higher Ed just a few days before A. J. Jacobs review of MOOCs and Frank Bruni's column on the purpose of higher education both appeared in the NYT.

Bruni writes about the debates at the UT flagship campus in Austin: Is college intended to provide job training, or something else? This is an open question, as lawmakers and educators in Texas, Virginia, Oregon, and many other states are increasingly interested in providing job placement statistics and salary figures for graduates with different majors. But, as some high-profile educators have pointed out, judging the worthiness of a college education by immediate post-college graduate earnings is far too narrow a metric. A liberal arts education does more than train someone for a job; it gives young people the skills to envision and invent the jobs they want, and it helps them become better global citizens and community members. But this view can certainly seem like a luxury, given the high numbers of unemployment for people under 25 and ballooning student debt.

I don't think anyone working in higher education today is unaware--at least to some degree--of the many stresses on both private and public higher ed in this country, and the difficult choices they are going to force.* And I certainly think instructional technology can provide pedagogically exciting opportunities to meet some of these challenges and to democratize education. The Jacobs piece, however, exposes some of the major issues that MOOCs present: attrition, isolation, and the idea that education is the same as content-delivery. If that's the case, then why not just do away with MOOCs entirely, and just skip to Wikipedia and YouTube? This is a slight exaggeration, but I do think that, at its core, this idea of education seems to be based around a "content-provider" platform. Professors provide the content, which EdX, Udacity, etc. then provide to the user. Content is static, not dynamic (the lectures, once written, recorded, and produced once, can be essentially "syndicated" and repeated every year or two). The other tacit assumption that this model rests on is that teaching and learning are scalable. This, it seems to me, is what the Amherst faculty found most at odds with their mission to provide education "through close colloquy." The scalability of education that MOOCs promise is also part of the "content-provider" model: I can watch content on my tv, my computer, my tablet, and my phone, anywhere I go (Jacobs addresses this explicitly). Education through "close colloquy" between students and faculty isn't scalable, and it's not portable. How long before we see EdX or Coursera partnering with Comcast or Time-Warner? Has that already happened?

*Indeed, I recently talked to someone who'd been at a large meeting with the president of an extremely wealthy, extremely prestigious private university. When asked by an attendee what the president was optimistic or excited about w/r/t the future of higher education, the president chuckled bleakly.

Bruni writes about the debates at the UT flagship campus in Austin: Is college intended to provide job training, or something else? This is an open question, as lawmakers and educators in Texas, Virginia, Oregon, and many other states are increasingly interested in providing job placement statistics and salary figures for graduates with different majors. But, as some high-profile educators have pointed out, judging the worthiness of a college education by immediate post-college graduate earnings is far too narrow a metric. A liberal arts education does more than train someone for a job; it gives young people the skills to envision and invent the jobs they want, and it helps them become better global citizens and community members. But this view can certainly seem like a luxury, given the high numbers of unemployment for people under 25 and ballooning student debt.

I don't think anyone working in higher education today is unaware--at least to some degree--of the many stresses on both private and public higher ed in this country, and the difficult choices they are going to force.* And I certainly think instructional technology can provide pedagogically exciting opportunities to meet some of these challenges and to democratize education. The Jacobs piece, however, exposes some of the major issues that MOOCs present: attrition, isolation, and the idea that education is the same as content-delivery. If that's the case, then why not just do away with MOOCs entirely, and just skip to Wikipedia and YouTube? This is a slight exaggeration, but I do think that, at its core, this idea of education seems to be based around a "content-provider" platform. Professors provide the content, which EdX, Udacity, etc. then provide to the user. Content is static, not dynamic (the lectures, once written, recorded, and produced once, can be essentially "syndicated" and repeated every year or two). The other tacit assumption that this model rests on is that teaching and learning are scalable. This, it seems to me, is what the Amherst faculty found most at odds with their mission to provide education "through close colloquy." The scalability of education that MOOCs promise is also part of the "content-provider" model: I can watch content on my tv, my computer, my tablet, and my phone, anywhere I go (Jacobs addresses this explicitly). Education through "close colloquy" between students and faculty isn't scalable, and it's not portable. How long before we see EdX or Coursera partnering with Comcast or Time-Warner? Has that already happened?

*Indeed, I recently talked to someone who'd been at a large meeting with the president of an extremely wealthy, extremely prestigious private university. When asked by an attendee what the president was optimistic or excited about w/r/t the future of higher education, the president chuckled bleakly.

Saturday, April 6, 2013

The Dystopic Future of Education Is Here

What an eye-opening week for higher education! Thanks to the folks at EdX, computers will soon be grading college papers.

"The system then uses a variety of machine-learning techniques to train itself to be able to grade any number of essays or answers automatically and almost instantaneously.

"The system then uses a variety of machine-learning techniques to train itself to be able to grade any number of essays or answers automatically and almost instantaneously.

The software will assign a grade depending on the scoring system created

by the teacher, whether it is a letter grade or numerical rank. It will

also provide general feedback, like telling a student whether an answer

was on topic or not."

It's true that I'm somewhat tempted by this; I'm looking at a very large stack of papers to grade this weekend. But this sounds like a bad idea for two reasons: The first is that offering feedback about whether a paper is "on topic or not" is not particularly helpful for a student who needs to learn critical thinking skills. Mastering a particular topic or some information is far less important than mastery of logic and rhetoric; additionally, the latter are ultimately transferable from one kind of task to another, unlike the former. The second reason is that I don't think the increased automation of education is a good idea. Or, put a different way, I don't think it's a good idea for learning anything other than basic content.

Not only is human-graded student work going out the window, but those entire pesky universities are, too. EdX is also teaming up with Pearson, the educational testing service, to offer proctored exams for certificate credit to MOOC enrollees. Yes, the for-profit education testing service is now going to be in the business of accrediting MOOCs for students who want to get academic credit. And the Minerva Project offers the promise of a "hybrid" model--MOOCs and a residential college experience. Pay for both experiences, but without getting as much as either has to offer by itself. The privatization of college education is here to stay.

Thursday, March 14, 2013

Game of Thrones Is Better on TV

I'm teaching a course on medievalism this semester, and one of things I've assigned is an episode of "Game of Thrones" (S1E7: "You Win Or You Die"). The books are too long to assign for a course that also covers a lot of other material, but I wanted the students to grapple with questions of adaptation; visual tropes of medievalism and high fantasy; and the presence of an interactive on-line community of fans and fan sites.

Adaptation (across media, time period, or country) is one of the through-lines of the course. Students read several different versions of the story of Merlin and Viviane, compare Chrétien de Troyes' Lancelot with Jerry Zucker's "First Knight," and look at medieval and contemporary stories of outlaws and crusaders. For our "Game of Thrones" and interactive fantasy unit, the students aren't reading any of the ASoIaF books, but they are digging deep into winteriscoming.net and other fan sites and wikis to research the characters they'll see in "You Win Or You Die." I hope that this will give them at least a basic introduction into the books and some of the choices that David Benioff and D. B. Weiss made when they adapted the books for HBO. I recently re-watched both seasons over again in preparation for this unit and feel even more strongly than I did before that the tv series is more interesting, more complicated, and more pleasurable than the book series.

There are a few different reasons for this. One has to do with the different media. The books are written in alternating third person POV, which gives the reader a limited view of the action and the other characters. A tv show can't do that. Although the show does focus on particular story lines or characters from episode to episode, it generally presents the action in omniscient third person POV (though there are some first-person POV camera angles). This means that characters whom we know (in the books) only from another character's POV (like Varys, Shae, or Jorah Mormont) become, instead, characters that we know just as well as Tyrion or Dany. This shift in perspective, combined with the talented cast and direction, makes the experience of the tv show richer. Martin isn't very effective at conveying the particularities of each character's interior life in writing. But the actors are *very* good. Jorah Mormont (Iain Glen), is embittered, protective, lethal, and a true believer in Dany's claim. Nikolaj Coster-Waldau made some specific choices as an actor to indicate Jamie Lannister's internal depths (and conflicts). This makes Jamie a much more compelling character than he is in the first two books of the series.

Another leg up that the tv show has over the books also has to do with the limitations of prose in general. Martin is a meticulous world-builder, but that requires an awful lot of description and exposition. Pages and pages of it. But the incredibly high production values on the HBO show mean that the art direction and set design can stand in for much of that description, and provide a richly inhabited and fully realized visual world. Sometimes the dragons look a little cheesy, but the Wall, Winterfell, and Pyke look fantastic. The limitations of Martin's prose, in particular, is another reason the tv show is better. The show's writers have condensed plots, dispensed with minor characters, and made the emotional resonances of the characters more complex. I think this is particularly true of a number of the women characters. It's not that Martin neglected Cersei, but the writers on the show have brought out her rage at being a pawn despite her considerable acumen, and this makes her villainy more plausible. She's a more nuanced character. Instead of the bland Jeyne Westerling, we get Talisa Maegyr of Volantis--an immigrant to Westeros out of conscience. It's also clear that Catelyn Stark has a canny mind for statecraft and diplomacy.

A lot of things still happen on the tv show, but the writers and producers make sure that the events always reveal something about the characters. Melisandre's shadow-assassin murders Renly, but the show gives us a sharp scene between Loras and Margery that illustrates Margery's pragmatism and Loras' anguish. Martin's books are like sprawling, paratactic medieval chronicles, but "Game of Thrones" is like a Victorian novel: it has narrative economy, coherence, and more richly developed characters. So, if you're not watching the show because you haven't read the books yet, skip the books and start watching.

Adaptation (across media, time period, or country) is one of the through-lines of the course. Students read several different versions of the story of Merlin and Viviane, compare Chrétien de Troyes' Lancelot with Jerry Zucker's "First Knight," and look at medieval and contemporary stories of outlaws and crusaders. For our "Game of Thrones" and interactive fantasy unit, the students aren't reading any of the ASoIaF books, but they are digging deep into winteriscoming.net and other fan sites and wikis to research the characters they'll see in "You Win Or You Die." I hope that this will give them at least a basic introduction into the books and some of the choices that David Benioff and D. B. Weiss made when they adapted the books for HBO. I recently re-watched both seasons over again in preparation for this unit and feel even more strongly than I did before that the tv series is more interesting, more complicated, and more pleasurable than the book series.

There are a few different reasons for this. One has to do with the different media. The books are written in alternating third person POV, which gives the reader a limited view of the action and the other characters. A tv show can't do that. Although the show does focus on particular story lines or characters from episode to episode, it generally presents the action in omniscient third person POV (though there are some first-person POV camera angles). This means that characters whom we know (in the books) only from another character's POV (like Varys, Shae, or Jorah Mormont) become, instead, characters that we know just as well as Tyrion or Dany. This shift in perspective, combined with the talented cast and direction, makes the experience of the tv show richer. Martin isn't very effective at conveying the particularities of each character's interior life in writing. But the actors are *very* good. Jorah Mormont (Iain Glen), is embittered, protective, lethal, and a true believer in Dany's claim. Nikolaj Coster-Waldau made some specific choices as an actor to indicate Jamie Lannister's internal depths (and conflicts). This makes Jamie a much more compelling character than he is in the first two books of the series.

Another leg up that the tv show has over the books also has to do with the limitations of prose in general. Martin is a meticulous world-builder, but that requires an awful lot of description and exposition. Pages and pages of it. But the incredibly high production values on the HBO show mean that the art direction and set design can stand in for much of that description, and provide a richly inhabited and fully realized visual world. Sometimes the dragons look a little cheesy, but the Wall, Winterfell, and Pyke look fantastic. The limitations of Martin's prose, in particular, is another reason the tv show is better. The show's writers have condensed plots, dispensed with minor characters, and made the emotional resonances of the characters more complex. I think this is particularly true of a number of the women characters. It's not that Martin neglected Cersei, but the writers on the show have brought out her rage at being a pawn despite her considerable acumen, and this makes her villainy more plausible. She's a more nuanced character. Instead of the bland Jeyne Westerling, we get Talisa Maegyr of Volantis--an immigrant to Westeros out of conscience. It's also clear that Catelyn Stark has a canny mind for statecraft and diplomacy.

A lot of things still happen on the tv show, but the writers and producers make sure that the events always reveal something about the characters. Melisandre's shadow-assassin murders Renly, but the show gives us a sharp scene between Loras and Margery that illustrates Margery's pragmatism and Loras' anguish. Martin's books are like sprawling, paratactic medieval chronicles, but "Game of Thrones" is like a Victorian novel: it has narrative economy, coherence, and more richly developed characters. So, if you're not watching the show because you haven't read the books yet, skip the books and start watching.

Saturday, March 9, 2013

The Quick and the Dead

Reports that the body of recently deceased Venezuelan president, Hugo Chavez, will be embalmed and placed on "permanent" display at the Museum of the Revolution have brought to mind other examples of this phenomenon. Other revered Communist leaders, such as Lenin, Mao Zedong, and Ho Chi Minh, received the same treatment after their deaths. And, of course, there are many examples of Christian saints whose bodies remain on display (or are brought out periodically).

Placing the bodies of particularly revered or heroic figures on display has a long history. In medieval historical writing (including historical chronicle and epic poems), heroic warriors from Troy and Carthage were embalmed (sometimes with magical fluids) and preserved for eternity. Hector, the prince of Troy, was placed in the open, where his subjects could see him. In one account, the embalming fluid went in at the top of his skull, and then flowed through his veins into his extremities.

-->

According to many natural philosophers, a person could not be considered fully dead until decay or putrefaction occurred. So keeping Hector perfectly "fresh" actually meant keeping him partially alive. Kind of like Han Solo in carbonite, or Wesley in "The Princess Bride."

Placing the bodies of particularly revered or heroic figures on display has a long history. In medieval historical writing (including historical chronicle and epic poems), heroic warriors from Troy and Carthage were embalmed (sometimes with magical fluids) and preserved for eternity. Hector, the prince of Troy, was placed in the open, where his subjects could see him. In one account, the embalming fluid went in at the top of his skull, and then flowed through his veins into his extremities.

|

| Hector's embalmed body. Cod. Bodmer 78, fol, 58r |

According to many natural philosophers, a person could not be considered fully dead until decay or putrefaction occurred. So keeping Hector perfectly "fresh" actually meant keeping him partially alive. Kind of like Han Solo in carbonite, or Wesley in "The Princess Bride."

Friday, March 1, 2013

Accusations of Vatican Corruption Are Nothing New

I've written before about how the persistent accusations against high-ranking Church officials of failing to report (or covering up) credible accusations of child rape and abuse at the hands of priests goes back to the Investiture Contest. But it wasn't until Joseph Ratzinger, formerly known as Pope Benedict XVI, retired that I realized that there are other similarities between the Catholic Church of the eleventh century and the twenty-first century.

A fascinating interview with Vatican beat reporter John Thavis on Fresh Air shed light on all kinds of possible conspiracies, cover-ups, misdeeds, and shenanigans. Cronyism is apparently pretty common, and there are many who think that this kind of petty corruption should not be part of the Church. In 2009, the former pope revoked the excommunication of a bishop who denied the existence of the Holocaust. Clerical sex abuse scandals have rocked Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Australia; in the US, Philadelphia and Los Angeles have seen indictments and resignations of high-ranking Church officials over this same issue. Some claim that Ratzinger knew far more about the extent of the abuse, and worked to cover it up before he became pope. The former pope's former butler was tried for leaking classified Vatican documents to journalists; these leaks led to recent revelations about wire-tapping of Vatican officials and authorized by the secretariat of state.

In the eleventh century, many clerics were disgusted by the corruption and immorality they saw in Rome. Cronyism, nepotism, and simony were rampant. Some popes were accused of necromancy, fornication, theft, and even murder. Many of these accusations were politically motivated, and some were leveled at popes after their deaths. But in the eleventh (and twelfth) century, the struggle for power was between the papacy and secular powers (such as the Holy Roman Emperor). Now the struggle is taking place within the Church itself.

A fascinating interview with Vatican beat reporter John Thavis on Fresh Air shed light on all kinds of possible conspiracies, cover-ups, misdeeds, and shenanigans. Cronyism is apparently pretty common, and there are many who think that this kind of petty corruption should not be part of the Church. In 2009, the former pope revoked the excommunication of a bishop who denied the existence of the Holocaust. Clerical sex abuse scandals have rocked Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Australia; in the US, Philadelphia and Los Angeles have seen indictments and resignations of high-ranking Church officials over this same issue. Some claim that Ratzinger knew far more about the extent of the abuse, and worked to cover it up before he became pope. The former pope's former butler was tried for leaking classified Vatican documents to journalists; these leaks led to recent revelations about wire-tapping of Vatican officials and authorized by the secretariat of state.

In the eleventh century, many clerics were disgusted by the corruption and immorality they saw in Rome. Cronyism, nepotism, and simony were rampant. Some popes were accused of necromancy, fornication, theft, and even murder. Many of these accusations were politically motivated, and some were leveled at popes after their deaths. But in the eleventh (and twelfth) century, the struggle for power was between the papacy and secular powers (such as the Holy Roman Emperor). Now the struggle is taking place within the Church itself.

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Book Announcement!

I'm pleased to announce that Medieval Robots, my book on medieval automata, will be coming to bookstores and the Internet in Spring/Summer 2014. It's official.

|

| My cat ate my book contract. |

Tuesday, February 19, 2013

Playing Those Medieval Robot Games

Google has alerted me to the fact that Starbound, a PC game that should be coming out in the next few months, contains medieval robots. The Glitch, a collective simulation of artificial, sentient, self-aware beings, were created by a god-like race to simulate the process of "civilization." But all of the experiments destroyed themselves, except for the ones that are still stuck in the Middle Ages.

I need your help here, folks. I know nothing about gaming, but this sounds awesome. If you have any information about Starbound or its world, let me know!

I need your help here, folks. I know nothing about gaming, but this sounds awesome. If you have any information about Starbound or its world, let me know!

Friday, February 15, 2013

Russian Meteorite Could Provide the Next Excalibur

Intense! That Russian meteor was bananas. Apparently, the bright explosion was perhaps caused by the amount of iron in it.

This meteor was unusual because its material was so hard — it may have been made of iron, the statement said — which allowed some small fragments, or meteorites, perhaps 5 percent of the meteor’s mass, to reach the Earth’s surface.

An enterprising smith could, under the right influences, forge this meteoric iron into a sword for the ages.

Fallen to earth in a falling star, a clap of thunder, a great burst of light; dragged still smoking to be forged by the little dark smiths who dwelled on the chalk before the ring stones were raised; powerful, a weapon for a king, broken and reforged this time into the long leaf-shaped blade, tooled and annealed in blood and fire, hardened...a sword three times forged, never ripped out of the earth’s womb, and thus twice holy.... (Marion Zimmer Bradley, The Mists of Avalon)

Except that apparently Terry Pratchett has already done this.

This meteor was unusual because its material was so hard — it may have been made of iron, the statement said — which allowed some small fragments, or meteorites, perhaps 5 percent of the meteor’s mass, to reach the Earth’s surface.

An enterprising smith could, under the right influences, forge this meteoric iron into a sword for the ages.

Fallen to earth in a falling star, a clap of thunder, a great burst of light; dragged still smoking to be forged by the little dark smiths who dwelled on the chalk before the ring stones were raised; powerful, a weapon for a king, broken and reforged this time into the long leaf-shaped blade, tooled and annealed in blood and fire, hardened...a sword three times forged, never ripped out of the earth’s womb, and thus twice holy.... (Marion Zimmer Bradley, The Mists of Avalon)

Except that apparently Terry Pratchett has already done this.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Using Computers to Date Medieval Manuscripts

A recent article in the Journal of Applied Statistics by two computer scientists and a medieval historian at the University of Toronto details their work using computer algorithms to date previously undated charters from the post-Conquest period in England. The researchers used the archive of dated early English charters at the University of Toronto to devise algorithms that can offer additional tools for dating medieval documents.

By using a data set that has dates attached, the researchers were able to compare their results with existing (and, presumably, accepted) data. They based the algorithms on specific phrases that appear in charters and that vary over time. A charter that had been dated by a medievalist as having been written between 1235 and 1245 was compared using the data from the training set, and was dated by computational methods to 1246.

It's fantastic to see another instance of humanists and scientists working together to solve historical problems. Archaeologists, paleo-epidemiologists, and biological anthropologists have been using scientific methods to shed more light on the bacterial cause of the Black Death and the reasons for its rapid spread in the 14th century. Yet the use of computational algorithms suggests several questions that remain to be answered. A specific question has to do with forgeries. Many medieval charters are forgeries. The most famous is the Donation of Constantine, which was discovered to be a fraud by the fifteenth century. It's not yet clear how a computer algorithm could help identify forged charters. Some may betray themselves with anachronistic phrasing, but others were written with enough care or close enough to the time that they purported to be from that looking for particular words and phrases would not uncover them.

Another, larger, question has to do with the way that text-based analysis and scientific methods can work together to shed new light on old questions. The Donation of Constantine was discovered to be a fraud by using similar methods: checking the language of the document itself. Two versions of the history of the Trojan War, widely accepted throughout the Middle Ages as being eyewitness accounts of the conflict (and more accurate than Homer's poetry), were unmasked as frauds in the early modern period--again, due to the efforts of scholars who painstakingly compared the texts with other, external data. It's not yet clear if computational methods are more accurate than what we might call scholarly expertise (though, of course, the scientists writing the algorithms are experts themselves), or computational methods offer more speed, and thus the ability to examine larger data sets. Both benefits can be enormously useful to medievalists. I can imagine that scholars working on projects that rely on charters as evidence might be grateful to have tools that could confirm (or call into question) their own chronology.

By using a data set that has dates attached, the researchers were able to compare their results with existing (and, presumably, accepted) data. They based the algorithms on specific phrases that appear in charters and that vary over time. A charter that had been dated by a medievalist as having been written between 1235 and 1245 was compared using the data from the training set, and was dated by computational methods to 1246.

It's fantastic to see another instance of humanists and scientists working together to solve historical problems. Archaeologists, paleo-epidemiologists, and biological anthropologists have been using scientific methods to shed more light on the bacterial cause of the Black Death and the reasons for its rapid spread in the 14th century. Yet the use of computational algorithms suggests several questions that remain to be answered. A specific question has to do with forgeries. Many medieval charters are forgeries. The most famous is the Donation of Constantine, which was discovered to be a fraud by the fifteenth century. It's not yet clear how a computer algorithm could help identify forged charters. Some may betray themselves with anachronistic phrasing, but others were written with enough care or close enough to the time that they purported to be from that looking for particular words and phrases would not uncover them.

Another, larger, question has to do with the way that text-based analysis and scientific methods can work together to shed new light on old questions. The Donation of Constantine was discovered to be a fraud by using similar methods: checking the language of the document itself. Two versions of the history of the Trojan War, widely accepted throughout the Middle Ages as being eyewitness accounts of the conflict (and more accurate than Homer's poetry), were unmasked as frauds in the early modern period--again, due to the efforts of scholars who painstakingly compared the texts with other, external data. It's not yet clear if computational methods are more accurate than what we might call scholarly expertise (though, of course, the scientists writing the algorithms are experts themselves), or computational methods offer more speed, and thus the ability to examine larger data sets. Both benefits can be enormously useful to medievalists. I can imagine that scholars working on projects that rely on charters as evidence might be grateful to have tools that could confirm (or call into question) their own chronology.

Thursday, January 24, 2013

How Early Modern Animal Jetpacks Went Viral